by Benji Rogers

I could never have imagined that the article I wrote would have the impact that it has, and I am humbled, stunned, and excited by the outpouring of interest and support that has come my way. In the short time since it came out, I have been overwhelmed by offers to speak publicly, offers of help and even offers to fund “what you are building.” So I need to be clear here before we begin: this is not something that I am building.

I am the CEO of an amazing company PledgeMusic whose amazing women and men solve what I refer to as the “first mile” problem of the music industry, by eliminating risk, creating engagement and giving artists both money and data to go off and make their music. In short, we help create the rights that the proposed .bc (or dotblockchain) format seeks to codify. This is a full time job, and it is one that I love deeply.

The “last mile” problem, which is the one that this project seeks to solve, is something that I care so very deeply about but that I could not solve on my own (even if I didn’t have a job already). This needs to be solved by all of us, an industry-wide initiative to fix the very problems that we created. I will do all that I can — mornings, lunches, nights and weekends — to advocate for it, but it’s not one person’s job. It’s our job, and that includes you who are reading this.

As such, I have created a staging area for this idea which can be seen at www.dotblockchain.info to help me get a handle on all of the inbound email that has come my way and also to solicit support from interested parties.

To recap: I proposed in the previous piece that we, the music industry, should create and own our own fair trade music format. Like the MP3 or the WAVthat came before it, but in this case a format that cannot be separated from its rights and still be played. I called this a .bc or dotblockchain codec. Within this codec would be the building blocks of a unified data set.

Anytime an artist or rights holder is ready to make their works available to the world, they would create a .bc file rather than a standard WAV or MP3. This would mean that all of the data needed to figure out who to pay, who owned what, and when it was created would literally be contained and/or referenced within the file itself. Once this step was completed all of this information would then be written into the blockchain and made available for all.

So we would, with a unified and fair trade data standard, create a Global Distributed Database of Musical Rights every time a song is encoded. This would mean that we—the artists, labels, publishers and musicians who created these works—would serve them to the world in the fairly-traded way of our choosing. Further to this, I proposed that VR, 360 Video and AR (Augmented Reality) would be the Trojan horse to drive both momentum and adoption.

Since writing this, we (and I’ll get to who that is later) have not only seen that this is all technically possible, but that we may even be close to an MVP that could get this whole thing kicked off. Below is an update to my initial concept based on meetings and feedback from all sectors of the industries involved.

1. It’s not a codec anymore. It’s a wrapper.

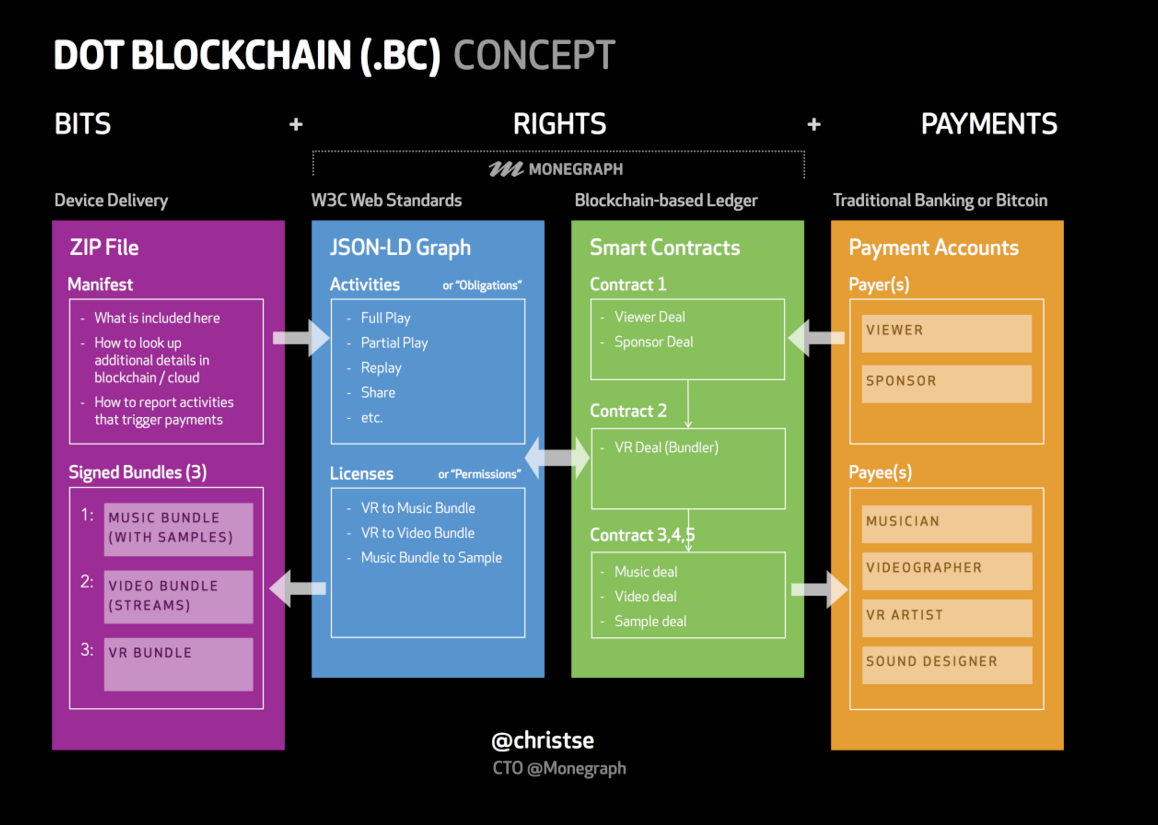

What we are proposing would not in fact be a codec but rather it would be a wrapper or container like a .zip extension that would perform all that is needed to ensure carriage of the MVD (Minimum Viable Data) into the blockchain. And it would we propose do this using the W3C web standardJSON LD. See below:

(and here on the web: https://monegraph.com/m6788760298)

Each .bc container could contain the hi-res, medium-res, low-res, stems, lyrics and associated data, etc making it possible for DSP’s and players to use the version that they require along with a manifest that would be mandatory for fair trade play or alteration. In effect: music with manifest = fair trade. Music without manifest = sweat shop.

2. Bitcoins Bad / Blockchain Good

Since this would be a format or file type, it can live on a number of blockchain solutions and not just the Bitcoin blockchain, although this is my current preferred solution. (The Linux Foundation’s latest release however is extremely compelling in this regard.) To add to this, it is not proposed that all of these .bc’s would live on the blockchain as this would not be possible or necessary even if it were. We propose therefore that these files would be deposited and would live in something like IPFS which would then in effect become our very own globally owned digital Library of Alexandria or Library of Congress. Since most of the transactions, changes and alterations to the data would happen using an existing W3C web standard, this would mean that the whole system would run fairly light and not bog down the blockchain. Monegraph has already built an elegant way of expressing this data within its existing architecture, so there’s no need to reinvent the wheel here.

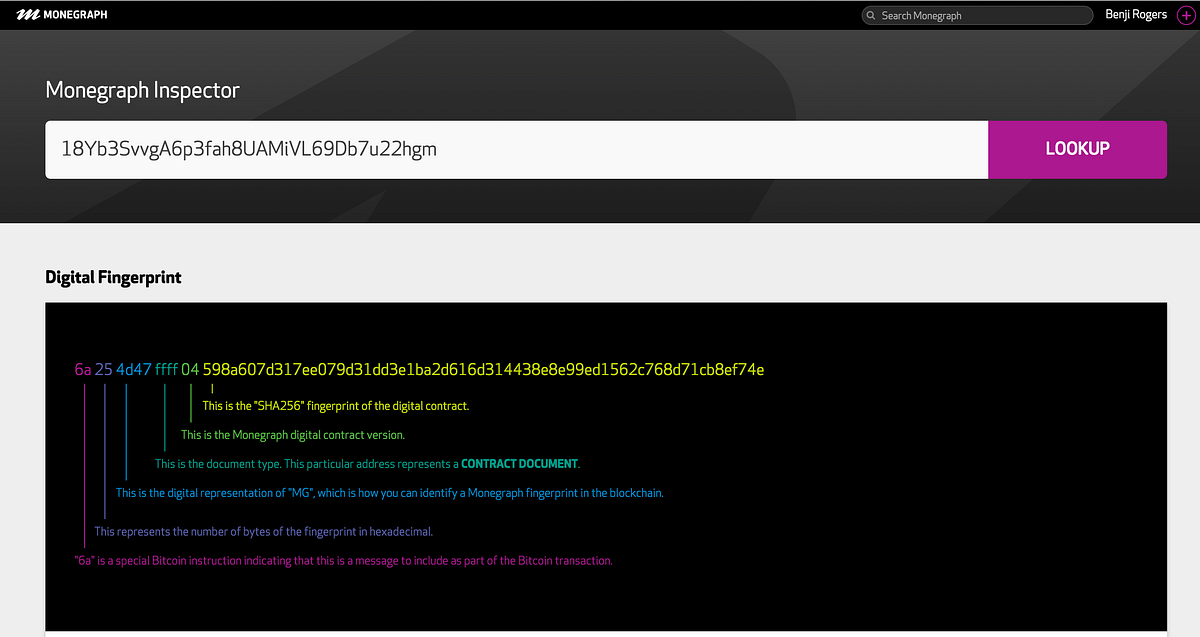

(The below image is a picture of the digital fingerprint for the diagram above which can be seen in browser here.)

With every .bc having its own fingerprint, it makes all of the above searchable and accessible to all in the blockchain, while still giving rights holders control over permissions and changes to basic rights through smart contracts. Being able to track changes in ownership and permissions in near real time is not only possible under this architecture, but will allow for new and enhanced uses for music across the digital ecosystem.

3. Digital Rights Management or DRM is really bad!

This has perhaps been the biggest issue I have encountered since this idea was proposed. It seems that DRM has created more than a few casualties! I have heard loud and clear, “Aren’t you just recreating Digital Rights Managementfor 2016?” To this my answer is categorically “NO!”

I am therefore calling this Digital Rights Expression, as none of what is proposed here is designed to limit possibilities. It is designed to augment them. What is proposed here exposes even more possibilities than the present formats in use, and this article would get much too long if I tried to list them all. But for the sake of clarity, .bc files would still be able to work on all current digital service providers platforms such as YouTube, Spotify, SoundCloud, 8Tracks, Tidal, Apple, etc. should this platform choose to accept them. You could even burn them onto a CD or cut them to vinyl if you wanted to.

What is proposed here is that, going forward, platforms would become .bc compliant, accepting only files that contain the correct minimum viable data within their file’s manifests. I believe that there is no good use case for a platform to want to traffic in files that do not contain such basic rights as ownership and who to pay. I further propose that it does no harm to the music ecosystem when platforms like YouTube or Soundcloud are suddenly able to monetize more of their content and platforms like Spotify, Tidal and Pandora are able to know exactly who to pay at the terms set by rights holders at the point of encoding or re-encoding. If there are platforms out there thinking to themselves, “Oh no! We know who wrote this now and who to pay. This is a disaster!” then I think their business model needs closer inspection. Much like today, when an artist uploads a song to TuneCore (now renamed MondoTunes), DistroKid or CDBaby in a standard WAV format for distribution, it is proposed that these services would either be served or would encode the .bc whose data could only be changed and altered by those who have permission to do so. As such this fits largely within the way things are done already.

4. Way too public and immutable?

One concern that I have heard voiced many times since the article came out is that all of this information would be way too public. First off an artist or rights holder only has to publish the minimum amount of data at the time of encoding. Once in, this information can be added to, amended or changed and these changes reflected in transaction trees (family trees) of ownership alteration in the blockchain. They can of course choose to put in as much as they like on top of the MVD, (Smart Contracts, exotic payment terms and usage preferences etc.)

If for example an artist or rights holder wanted to tell people how much they could license a song for then they could do that. If they wanted to simply be contacted to make a deal, then they could express that wish in the rules alongside the means to do so. In any case the proposed architecture contains a secure permission and access system, which would allow the relevant rights owners to choose to reveal or not reveal certain or all of their data on the blockchain, while maintaining the ability for all users to understand who owns the rights to the music. At present, most files contain almost zero contact data, so I am a big fan of making basic contact and payee information a part of the MVD.

Another concern has been voiced around the uploading of incorrect and or incomplete data especially as it pertains to publishing ownership. I am proposing that at the time of upload proof of ownership be required by at least one of the publishers or owners representing a work. This would in essence anchor the .bc into its place in the blockchain and should a dispute around ownership arise, then the blockchain database and the MVD contact information would allow any future conflicts to be sought out and resolved.

To avoid duplication of works, in the previous article I also proposed that all works going into the system would go through multiple databases (Shazam,Dubset/MixScan (esp for derivative works), Gracenote etc) on the way into the system and that they should be distinctly classified once through. Whilst it is anticipated that a small minority of songs will still make it through any such filters and scans at the very least there will be one central place to find and dispute any claims that arise, because, well, quite simply you would know where to look. Further, were someone to attempt upload of a work that is already in the system—for example uploading an MP3 to YouTube or Soundcloud and the ID matched an existing .bc of the work—then the digital service provider in question wouldn’t need to use the non-compliant version. They could (like iTunes Match already does) serve up the verified and owner/payee identified version instead. So in theory with one place to look for proof then only one version of the song would really ever be required creating a greater efficiency across existing and future networks of distribution and payment.

5. What about those who profit from a lack of transparency?

There is and has always been a big business in delaying or, in some cases, not paying artists and songwriters at all. As I have been sharing this idea, more stories of how this is true seem to come to light every day. A strong argument could be made that this very fact dooms the .bc project to failure, and I have had some of the most heated debates over this side of the coin — especially from the artist’s camps.

What I propose in answer to this is that, for the first time in the history of the music business, the money being left on the table is dwarfing the money being made under the table. In other words, when you see the sheer volume of un-monetized use as it compares to the trickle that is getting through the door at the moment, then the argument for a more transparent and open system becomes purely economic (not that this is the only good reason to have it.)There is more money to be made in a transparent system, and I don’t believe that this has been the case until quite recently. Add to this the size and speed of deployment of 360 video, VR and AR, and I think it’s very clear that what is made by hiding money today is by far eclipsed by what could be made tomorrow.

7. Who would do it?

In my initial presentation of this to friends and colleagues, I posed the question that any kind of global database of rights would be amazing to have, but who would build it?

Since the article came out, I have met with people representing performing rights organizations, governments, labels, publishers, blockchain and blockchain 2.0 companies, lawyers, academics, social networks, VR companies, agents, songwriters and their associations, artists and their associations, management groups, VC’s and journalists, aggregators, digital service providers and, perhaps most exciting of all, music fans. In this mix, the idea has been met with an overwhelming amount of positivity and constructive criticism. Not one person has flat out shunned the idea and, in fact, almost all have offered to help. I believe people see the idea of a fair trade music industry format and standard anchored in data to a blockchain as an idea that is good enough to agree on. For those of you who are not in the music industry, please note that agreement about pretty much anything is and always was hard to come by!

Also since the idea was presented, many brilliant people have added to it and we are now at the stage in the game in which we have a rough technical spec (see above or here) that was created by Chris Tse of Monegraph. We also have broad agreement on putting this voluntary survey out to all of the stakeholders in our industries to get their views and feedback on this idea and more importantly on what the Minimum Viable Data Standard should include in order to classify a media file as “fair trade.” Links to the survey are here and will be sent to anyone on the www.dotblockchain.info mailing list. We welcome your input.

It is worth mentioning that there are a number of private companies (current count is over 20) that are charging into this blockchain and music space, each with their own solution to the larger problems that lie before us. None of these, however, are looking to solve this at the specific format level, and most have agreed that they would like to participate in the dotblockchain project. As such I have enlisted the help of Ken Umezaki, from Digital Daruma, Christ Tse and Bill Wilson along with others to be announced with the intention of setting up a public-benefit corporation that would undertake the work of getting this from an idea in a blog to a usable format. The holding page for this new entity can be found at www.dotblockchain.info as well as an e-mail list from which updates will be sent.

As I have stated before, we would like to get consensus on what Minimum Viable Data would be by the end of Q2 of 2016 and a working MVP out to the open source community by the end of Q3 of this year.

If we as an industry can gather around a first kernel of truth, and then build the infrastructure to move this idea forward then everyone will benefit. If we as stakeholders in this industry are able to create and own the format in which we share our music with the world, then we change our destiny rather than just continuing to be subject to our legacy. Technologies will soon scale as we have never seen before, and the consequences of inaction at this time would be disastrous.

Digital Rights Expression begins with a song. A song that is encoded into a format that we all own. A format that contains the rights within it as expressed by its creators and owners. And this process drops, one by one, all of the music that we make into a global and distributed home for all of our musical and artistic wealth. A home that serves all players in the game — not just the largest but also the smallest, and it all begins with the first song to hit this system. A song whose ownership can be proven, whose rights cannot be removed, added to, amended or altered without the permission of it’s owners. The alternative is just more of the same. More instability, more alteration, and a further lack of transparency but at a scale unlike any we have ever seen.

Read part one here.